In reply to Demi about his general topic, without having spent a day in his class, I'll take a completely different position:

1) Public Choice theory, which seems to be the main crux of his argument (and the main bulk of research out there), is basically wrong about decision-making among public officials because the budget deficit (or surplus) is largely endogenous due to:

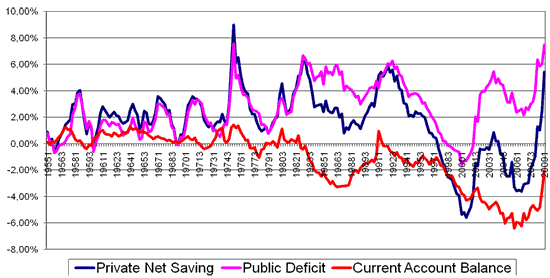

2) Economic factors, measurable in things like savings rate, credit expansion, business and household investment, and trade patterns for the particular Public Entity in mind (Whether it be a country, state/province, municipality, etc.). If you look at national accounting identities for example, it is easy to see the simple pattern of US public deficits and surpluses closely match patterns in changes of trade deficits and surpluses, best seen and accounted for as a percent of GDP, also called Sectoral Balances:

Thus additional private investment and consumption could help out a public entity improve its bottom line by increasing tax receipts and (depending the type) decreasing benefits, regardless if said investment and consumption is of the desirable kind (as the late 90s and mid 2000s have forewarned). Additionally, you could improve the Current Account, usually achieved through producing and exporting more goods through trade, or attracting dollars from outside to spend locally.

And as we've seen some nations without their own sovereign currency like Spain, who operationally function similar to a US State or a Canadian Province, have their housing bubbles mask a large current account deficit:

So one standard argument is to lower wages in order to lower the CA deficit by reducing the unit cost of domestic(or within the public entity) goods for export and import substitution. That of course can run into problems of debt-deflation, with falling private investment and consumption, less tax revenues, and even some problems of hysteresis. In some cases, cutbacks in public expenditure also leads to a negative multiplier effect in private demand that makes the initial cutbacks self-defeating defeating in terms of revenue (see: PIIGS).

However, except for nation-wide governments that control and can print their own currency, large budget deficits that occur from largely exogenous economic factors are at the mercy of the 'Bond Vigilantes'. Financial space for additional spending or cutbacks primarily depends on that government's credit rating and ability to find people to buy their bonds, as well as other higher-up political forces. And ultimately, some kind of public policy to improve the CA to balance is often what ultimately stabilizes these public budgets in the first place.

But how policy makers ultimately determine how to act with public finances, one must take the:

4) Statutory Constraints imposed on taxation and spending, as well as institutional functions and executions, the various political coalitions and vested interests to guide future changes, and the prevailing Attitudes and Ideologies that guide public policy decision-making.

So one could look at the debt ceiling imposing an artificial constraint on spending, one that is often changed every year by Congress. Many of these laws are not completely purposeful, but path-dependent and the result of political circumstances from ancient to recent history. 49 States in the US now have, as you said, a balanced budget amendment, some instated more recently than others, producing its own set of political behaviors (more on this). And finally, the Eurozone has a 3% fiscal deficit maximum as agreed to by Maastricht, an idea finding much of its roots through Germany's political influence and the Freiburg School of economics. In the latter two cases, this is largely a political response, well supported by the public, to prevent the possibility of profligate public financiers from creating a solvency crisis.

And, some of the public policy responses to this Maastricht Fiscal Deficit requirements were to hide it off the balance sheet (hey Greece!) or simply allow housing bubbles to make the situation seem better than it actually was. Also one thing to compare would be the Troika "structural adjustment" reforms with Germany's own Agenda 2010.

The States on the other hand are basically forced by statute to be expansionary during boom times and austere during slumps. Precisely HOW they are expansionary and austere depends first on the path-dependent spending patterns, i.e. pensions, prisons, social welfare, interest payments. Then, depending on the public administrator's Political Coalition and its vested interest, prevailing ideologies and personalities, they'll expand or cutback. Thus, during the boom years of the last 3 decades, many governors cut taxes during boom years while cutting education in slump years, while prison, pension and medical spending increased regardless of political party. Yet you can still see significant changes based on different state-wide coalitions and governors with certain ideas.

Anyhow, that would be my approach to your topic. I don't know if you'd be interested it in though, since the literature on these ideas is thin yet the subject is pretty complex, or maybe you could incorporate some of it into a sort of 'Devil's Advocate'. Good luck either way you go!

I'd add it mainly because it supports my point that even though it is a good idea, it's ultimately unfeasible given that deficits are a product of systemic constraints imposed by the economic and political systems we live in rather than a culture of profligacy or Congressional immorality

ReplyDeleteAlright cool, I'll try to get you some links to some stuff that may expand on my point. I know there are some good presentations on youtube by, for example, Richard Koo and Lord Skidelsky, that would go further on the Sectoral Balances in Spain, or Skidelsky talking about "Power". Plus you might as well look up guys like Wynne Godley or Marc Lavoie, since they sort of invented the Sectoral Balances approach..

ReplyDeleteYou should also check out Summers-Bernstein's relatively recent (2 years ago?) paper that fiscal austerity during a slump may be self-defeating in purely fiscal terms, and you can cite Southern Europe as an example. etc.

There's definitely something to be said for the difficult-to-alter nature of deficits and spending in particular. A lot of people compare government finances to household finances, but in truth, households cut spending easily. Governments cannot, given their own incentives and legal constraints.

ReplyDeleteTo this end, though, I believe that external or Constitutional limits on borrowing authority really CAN help. One that pops to mind is the independence of the central bank, which really does have an impact on macroeconomic outcomes and fiscal profligates.

Governments that do not run their own central banks cannot simply monetize their debt and therefore are subject to some spending constraints.

Perhaps a decisive factor is the actual strength of the constraint and who is imposing it. For example, Congress cannot simply vote to lower spending, and expect it to stick, because a future Congress can simply vote it up. Mandated increases, like you mention Kain, are a way to increase spending in a way Congress can't really fight...much harder to get any momentum on those.